Summary

Horses help people build skills and confidence by offering calm, responsive interactions that encourage communication, focus, independence, and emotional awareness. This guide explains how equine-assisted activities create supportive, meaningful experiences that help riders grow at their own pace.

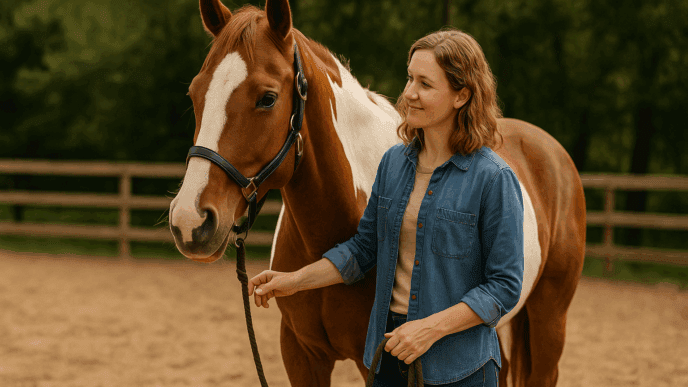

Horses have an extraordinary way of helping people feel capable, grounded, and connected. Whether someone is brushing a horse for the first time, learning how to guide a gentle walk in the arena, or participating in a structured riding lesson, horses naturally encourage growth in ways that feel genuine and deeply personal. They respond to human body language, energy, and intention, creating a powerful learning environment that blends communication, trust, and movement.

For many riders, especially those participating in equine-assisted activities, time with horses becomes a place where confidence is nurtured step by step. Riders discover that the horse listens to them, responds to them, and moves with them. This realization often brings a sense of accomplishment that is difficult to replicate anywhere else. At its core, understanding how horses help build skills and confidence begins with the way these animals interact with people — quietly, consistently, and without judgment.

The Natural Relationship Between Horse and Rider

A horse communicates primarily through body language and small, subtle cues. Riders quickly learn that their posture, tone of voice, and clarity of movement make a difference. When a rider sits a little taller, relaxes their shoulders, or steadies their hands, the horse often responds in kind. This cause-and-effect relationship encourages riders to become more aware of their actions and how those actions influence the world around them.

Unlike many everyday situations where feedback can feel overwhelming or unclear, horses offer simple, immediate, and honest responses. If a cue is gentle and clear, the horse may stop, turn, or move forward with calm intention. If the cue is confusing, the horse might pause and wait for clearer direction. This dynamic helps riders recognize their strengths, practice communication, and gain confidence through direct interaction.

Building Confidence Through Familiar Routines

One of the most reassuring aspects of equine-assisted activities is the predictability of the routine. Riders arrive at the barn, greet the instructor or volunteers, meet their horse, and begin their session in a familiar manner. These repeated patterns help riders feel secure, especially those who benefit from consistency and structure.

Simple routines — brushing a horse, placing a saddle pad, or walking together toward the arena — often become landmarks in the session. As riders grow familiar with these steps, they develop a sense of independence. Tasks that once felt intimidating become manageable. Over time, the barn becomes a place where riders know what to expect, and that predictability is a strong foundation for building confidence.

The Power of Movement

A horse’s movement is rhythmic and steady, and riding creates a sense of connection that can be both energizing and calming. The gentle sway of the horse’s walk encourages balance and body awareness. Riders learn to adjust their posture, hold the reins with intention, and stay centered in the saddle. As they become more comfortable with the horse’s movement, they often feel more confident in their own abilities.

Small achievements — maintaining balance for a full lap, steering through a simple pattern, or bringing the horse to a smooth stop — become meaningful victories. Each accomplishment helps riders trust themselves a little more. Progress does not have to be dramatic to be significant. The horse’s consistent rhythm helps riders build skills gradually, with each session reinforcing the one before it.

Communication and Trust

Horses thrive on clear communication. They do not judge or criticize — they simply respond. This creates an environment where riders can practice giving instructions, expressing themselves, and learning to read another being’s behavior.

For someone who struggles with confidence, the moment a horse responds to their cue can be transformative. Realizing that a simple voice command or shift in body position can influence a 1,000-pound animal is a powerful experience. It tells the rider: “You are capable, you are heard, and you matter.”

Trust also flows both ways. Horses learn to trust their riders through gentle handling, calm interactions, and consistent cues. As this trust develops, the relationship becomes a partnership. For many riders, especially those who may feel uncertain in other areas of life, gaining the trust of such a sensitive and perceptive animal builds deep confidence.

Skill Building Through Hands-On Experiences

Equine-assisted activities are full of opportunities to build practical skills. Grooming teaches gentle touch, attention to detail, and awareness of the horse’s comfort. Leading a horse encourages clear direction and steady movement. Tack preparation introduces responsibility and sequencing.

Even small tasks, such as fastening a girth or placing a halter correctly, help riders practice problem-solving and follow-through. The barn environment supports learning in a natural, hands-on way. Instead of being told what skills to build, riders experience these skills directly through meaningful interaction with the horse.

Mounted activities expand these skills further. Riders learn spatial awareness as they navigate the arena. They practice decision-making as they choose when to turn or stop. They develop perseverance as they work toward steady posture or smoother cues. Over time, these moments add up, helping riders feel increasingly capable and confident.

Emotional Growth and Self-Expression

Horses respond to human emotion with remarkable sensitivity. They notice when someone is tense, relaxed, hesitant, or excited. This awareness creates opportunities for riders to explore their own emotions in a safe and supportive environment.

Many riders find that the barn becomes a place where they can express themselves freely. Horses do not judge tone or mood. They simply respond to the energy presented to them. For individuals who may feel misunderstood or pressured in other settings, this unconditional acceptance can be incredibly empowering.

Emotional growth often appears in small but significant ways — a rider who begins to speak more confidently, a participant who learns to take a deep breath before giving a cue, or someone who discovers they can stay calm even when a situation changes. Horses help riders slow down, tune in to their feelings, and build a sense of inner steadiness.

Growing Independence Over Time

As riders continue participating in equine-assisted activities, many begin taking on more responsibility. They may lead their horse independently, help prepare equipment, or ride with less support from volunteers. These milestones show riders that they can achieve new levels of independence at their own pace.

The barn is full of tasks that look small from the outside but feel significant to the person experiencing them. Closing a gate, carrying a brush box, steering a horse through a pattern, or riding a full lap without assistance are moments of progress that build real confidence. Each step reinforces the idea that growth is possible — and that the rider is capable of more than they may have imagined.

A Supportive Community

Equine-assisted activity centers are communities built around encouragement and inclusion. Riders interact with instructors, volunteers, other participants, and, of course, the horses. These relationships create a sense of belonging. Riders feel supported not just by the horse beneath them but by the people cheering them on.

This community aspect deepens the confidence-building process. Riders often develop friendships, celebrate each other’s progress, and share experiences that strengthen their sense of connection.

Why Horses Make a Difference

Horses help build skills and confidence because they offer something rare — immediate, honest feedback in a setting that feels calm, structured, and welcoming. Their presence encourages riders to slow down, stay grounded, and explore new abilities. They make growth feel natural, not forced.

For many people, the moments spent with a horse become some of the most meaningful parts of their week. Whether it’s mastering a new riding skill, brushing a mane, or simply standing quietly beside a horse, each interaction helps build a foundation of confidence that extends far beyond the arena.